Art as a tool for healing immigration trauma

The work of Arlene Correa Valencia and Sandy Rodriguez

Arlene Correa Valencia, “We are the Protectors,” 2023

Hi friend,

The recent uptick in racists, demeaning insults hurled at immigrants by right-wing politicians is hideous. I refuse to repeat them, but when MAGA-endorsed speakers and presidential candidates (I shudder) chide Puerto Ricans, Haitians and all “Latinos” it triggers me as an immigrant and a Latina. As you may have noticed, there is a subconscious thread running through this newsletter - it highlights artists whose work I see as vital to the decolonizing narrative. And studying how artists interpret immigration in their work is both illuminating and vital in this political climate of hate.

I came to the U.S. from Ecuador when I was five years old. Quito is the quintessential colonial town, conquered and then re built in the sixteenth century on top of pillaged Incan ruins. I was born there in the early 70’s and my mom worked in a law firm with big oil as their client. We ended up in Dallas, Texas because my American step father- an oil executive- was making regular trips to the region- specifically (and tragically) the Amazon region. Anyway, I left Quito in 1975, and not knowing a word of English, I immigrated to a very white suburban Dallas. Thanks to public school, PBS (a combo of Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers taught me English) I “assimilated” after a few months once I learned the language. I remembered hiding the fact that I spoke Spanish since the elementary school I attended had no Latinx kids. Because I had the priviledge of a green card I returned to Ecuador every summer and grew up thinking this fluid border crossing of language and culture was the norm. This is why the current anti-immigrant rhetoric is giving me PTSD of the 2020 Trump administration’s treatment of immigrant kids that was especially appalling to me.

It is hard to fathom the terror and sadness children and parents experience in face of forced separation and war. The U.S. government, among many others, has made crossing borders traumatic and cruel. In the U.S. have lived in states that thrive on immigrants: Texas, Florida and New York, all culturally rich because of the diversity of languages and culture. A plurality which would be inconceivable without immigration, since in this country, with the exception of Native Americans, we are ALL immigrants.

Art is the custodian of the constellation of risk; the timekeeper of the recurrent now…now…now. Art doesn’t only alter our views; it arrests our line of sight.

-Homi Bhabha

Art and writing are two places I gravitate towards when confronted with the unfathomable (like what is at stake in this election). I want to talk about two female artists whose work deal with immigration and violence and also recommend two books, also by women writers, that helped me gain a deeper understanding of the trauma inherent in living as an undocumented migrant. I will start with Napa Valley-based activist and artist Arlene Correa Valencia. Born in 1993, her family immigrated to the United States in 1997 from Michoacán, Mexico. Originally trained as a painter, her mother-in law taught her to sew during the pandemic since she could not get to her painting studio. This was pivotal to her current textile-based work (see below) incorporates clothing remnants of fabrics worn by people who have experienced family separation.

The faces that populate her current work are covered in blank fabric, or “blank slates.” Almost inviting the viewer to inscribe meaning and context to the often invisibility surrounding the undocumented. In fact she describes her community activism and art as changing the narrative on the “invisibility of undocumented migrant workers.” Her own upbringing in an agricultural community, and her own forced separation from her beloved father at a young age, inform her politically prescient work. Reflecting on her own family’s mixed immigration status in California’s Napa Valley, she uses clothing remnants, parts of the reflective vests used by agriculture workers, archival family letters, collaborations with Mexican artisans and her own father to illustrate how migrant families are literally woven together despite cruel immigration policies. Watch this YOU TUBE to hear more about her inspiring story.

When asked about her work for a recent article she said this:

“My work explores the nuances of migration, visibility, invisibility, borders, and family separation through various mediums including textiles, social practice, and painting. After living in the United States for more than 25 years as a registered illegal alien, I use my family’s story to subvert the language and ideas that are assigned to immigrants.”

Cuarto de Reunion #1: No Te Preocupes Hermanito, Ahorita Nos Toca a Nosotros. Volveremos a Ver a Mama y Papa. / Reunification Room #1: Don’t Worry Little Brother. It’ll Be Our Turn Soon. We Will See Mom and Dad Again., 2022, Repurposed textiles on black canvas, 72 x 52 inches.

“For a while now I had been thinking about how I constantly introduce myself as undocumented, and naturally the work that I do in many ways has helped me let go of the weight of being labeled ‘illegal.’ As migrant people we have learned to live in constant fear and shame. Policies have made us believe that migration is a crime and in turn we become criminals. This idea of not belonging because of the lack of documentation is one that carries an immense amount of embarrassment and discomfort. Recently I asked myself "are you really not ashamed to be undocumented anymore?" In an attempt to be honest with myself, (and don't get me wrong I wanted so badly for the answer to be yes, yes I'm not ashamed anymore), I found that I had been shying away from having this "coming out" conversation with new friends because I was too ashamed to admit who I am politically. I was, and still am, living under the same fear that people will see me as less than because of my status. I am living blanketed by a thick layer of shame.” - ACV

25 Estrellas: Sueños Para Mi Hija / 25 Stars: Dreams For My Daughter, 2022, repurposed American Flag on canvas, 60 x 50 in

Arlene is represented by Catherine Clark Gallery in San Francisco.

Raised in San Diego, Tijuana, and Los Angeles, Sandy Rodriguez (b 1975 National City, CA) is a first-generation Chicana and a third-generation artist who was raised on the U.S. Mexico border. Her maternal grandfather, who was adopted by a Catholic priest as a child, made religious imagery in Tijuana. Her grandmother and mother are also an artists, in fact she and the latter went to school together in San Francisco!

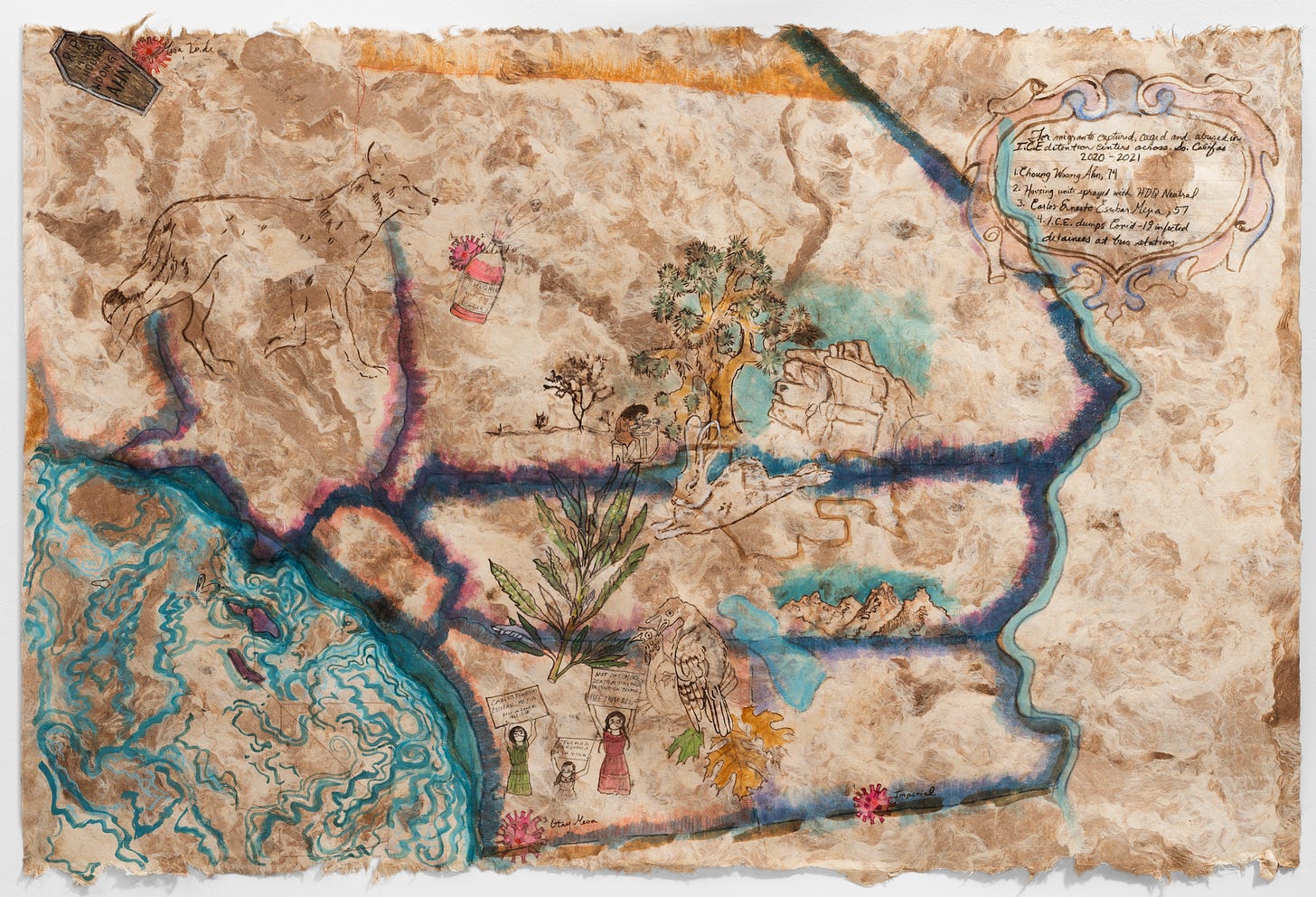

Her work engages deeply with colonial archival material, specifically the Florentine Codex. This Spanish colonial document is a sixteenth-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica complied by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. In her work, Sandy Rodriguez re interprets these colonial codices as current socio-cultural maps which include indigenous flora and fauna that she documents like a modern-day scientific expedition.

Her work is deeply political as it deals with violence and immigration. It personifies the healing potential of art on so many levels. On camping expeditions throughout California she physically collects native botanical specimens, many medicinal in nature. She then produces her own pigment paint with earth, and with this act she unleashes the “possibilities for healing past and present trauma through the recovery of Indigenous knowledge systems." She not only recovers ancestral knowledge she extracts color from plants, insects, seeds, minerals, and soil. This brilliantly shows the layers of history behind a painting. She then utilizes her work to call out and educate people on the border violence perpetuated in the present day. This merging of historical and current events makes her art vital in understanding the current debate over identity and belonging, especially with regards to border culture by providing the viewer with a space to reflect and heal.

(Read this article from the L.A. Times called “How artist Sandy Rodriguez tells today’s fraught immigration story with pre-Columbian painting tools.”)

Sandy Rodriguez, Map for the Migrants Captured, Caged and Abused in I.C.E. Detention Centers in So. Califas, 2020-21 (from Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón, 2017- ), 32.5 x 47 inches, hand processed watercolor on amate paper. Image courtesy of Studio Sandy Rodriguez.

“We’re reclaiming and reaffirming the indigenous artistic practices of the Americas…In my work, a multitude of records and documents and maps are combined and juxtaposed to really inform an interpretation of space where all of this is recovered, reinvisioned and painted as a codex — a macro and micro view of humanity in relationship to time, power and land.” - Sandy Rodriguez

The natural red and brown dye cochineal that she uses in most of her work is produced by an insect that feeds on cactus, it is part of her pantheon of Pre Colombian indigenous color traditions that she has taught herself. She describes her innate connection to her materials, both the paper and the actual paint as a communion which creates path towards healing trauma.

Her paper “canvas” is Amate a handmade bark paper that has been manufactured in Mexico since before colonization. Banned by the Spanish crown, (its use was punishable by the death penalty) as a way to erase the historical memory of Mesoamerica. To make it fibers are cooked and beaten and pounded together with a stone. She describes it as “outlaw paper.”

In 2017 her work took a shift when she became a full-time artist after a long career in Museum Education. It was after that when she merged her art with her educational background to create these haunting and beautiful portraits of migrant children who died in US Customs and Border Protection custody. (see below and read more here) Also made on amate paper, these pieces honor the lives of the children as well as their Guatemalan heritage. On the bottom left she includes a green quetzal birds, a symbol of freedom for the Maya who would capture the birds, pluck its feathers, and release them back into the wild. According to the artist, the bird “dies from sadness when caged.” The allusion to the fate of the children could not be more poetic.

Sandy Rodriguez, Juan de León Gutiérrez (age 16, a child migrants who died in federal custody between 2018 and 2019), 2019. Hand-processed watercolor on amate paper.

There are seven portraits in total of the Central American child migrants who died in federal custody between 2018 and 2019. Most passed because of communicable illnesses due to inhumane conditions and overcrowding at Customs and Border Patrol holding areas in the Southwest of the U.S. In the portraits she includes the full names of each child as well as their birth and death years. In making the invisible violence visible her work echoes that of Arlene Correa Valencia, who also, through the chosen material of discarded garments, makes the reality of immigration trauma tangible. I am in awe of their work and I encourage you to follow them on social media.

**Great news for Florida, Sandy Rodriguez will be in a 2025 show at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, I promise a longer piece on her work soon!

There are two women writers whose work has profoundly affected the way I understand the trauma of living as an undocumented American, work of Ecuadorian-born Karla Cornejo Villavicencio and Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticant. I cannot recommend these books enough, buy them (from a local bookstore) and thank me later.

And while on the topic of epic Mexican-American artists, a huge congrats to Willy Chavarria who has won CFDA menswear designer of the year for the second time in a row!! Listen (podcast linked here) to this BOF podcast about fashion as a tool for social justice is the BOMB as is Willy’s stylish cool af Chicano style! BRAVO!

Thank you for being here, and please vote.

With much love, Vero

Thank you for sharing the art of Arlene Correa Valencia. I was about to toss my phone down in exasperation for another much-needed break from our current devastating news cycle, and I found your article, Vero. Seeing Valencia's work reinforces my faith in the healing powers of art and creation to often (even literally!) sew together our rended spirits in this hateful and fractured time. It helps give me the energy to get to my studio this morning, and to keep up fighting the darkness with the beauty and permanence of art.

The piece written by Verónica is as powerful as the times we’re living. It shows the power of her roots, plus the immense knowledge of art and writing skills 👍🏼