Calling Latinx Art "Hispanic" is a misnomer

notes on identity + the Latin American and Latinx Art market

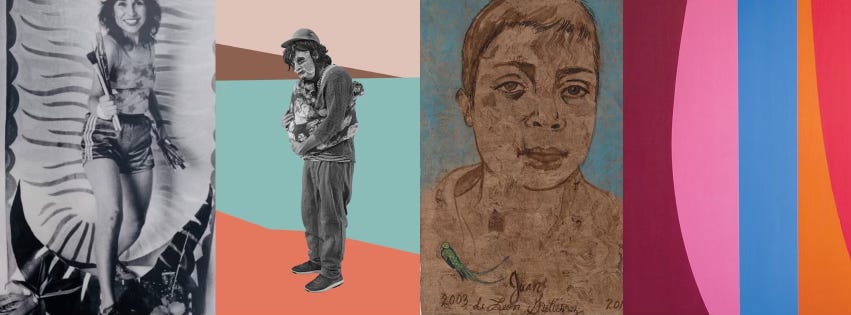

(From L to R: Yolanda López, Zilia Sánchez, Edison Peñafiel, Sandy Rodriguez, Fanny Sanín)

This newsletter is a follow up to a panel discussion that I moderated last week in Miami, the subject: “Latinx” Art during “Hispanic” heritage month. Let’s start with the word “Hispanic” which is a derivative colonial term stemming from the Latin word Hispanicus, the adjective form of Hispania, the ancient Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Linguistically speaking, it’s use implies that people of Latin American descent living in the U.S. are from Spain. By looping all of us into one monolithic category it white washes and excludes the myriad racial, social and cultural complexity of both the U.S. Latinx population and “Latin” America. It also implies a hegemony of the Spanish language, and ignores the 211 million Portuguese speakers in Brazil, the Haitians who speak creole and the hundred of indigenous languages spoken throughout both North and South America. (Brazil alone has about 186 indigenous languages, Mexico has 67, Colombia more than 65 and Peru has 47.)

Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Coco Fusco perform Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West, in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, September 12, 1992. Photo courtesy the Walker Art Center

In 1988 Reagan signed “Hispanic Heritage month” into law, and almost 40 years later, we are still grappling with the terminology. Personally I prefer the term Latinx over Latina/o because it is more inclusive, and I agree with Arlene Dávila in her seminal book on Latinx art: “the X factor helps to center the experience of Latinx diasporic identities which remain most invisible” in the world of contemporary art. X is a site of intersection that allows space for the inclusion of a diversity people. I would guess that the actual percentage of people of Latin American descent living in the US who identify as “Spanish” (as in European) is quite small. Hispanic as a blanket term needs to be retired as the “official” nomenclature for a month designated to recognize 20% of Americans who identify as Latinx. In terms of the art market, Dávila frames “Latinx” art as a PROJECT, not as a fixed identity and her goal is point out how gatekeepers like galleries, museums, Academia and the mainstream art market have not been inclusive of Latinx art. According to several studies of major U.S. museums, Latinx artists represent only 2.8% of artists in museum collections, a massive underrepresentation. It is time to expand and problematize the “dominant categories of contemporary art” which, in a nod to patriarchy, have traditionally favored the narrative of “great” male artists from Manet, Monet to Picasso and Pollack as the chosen ones.

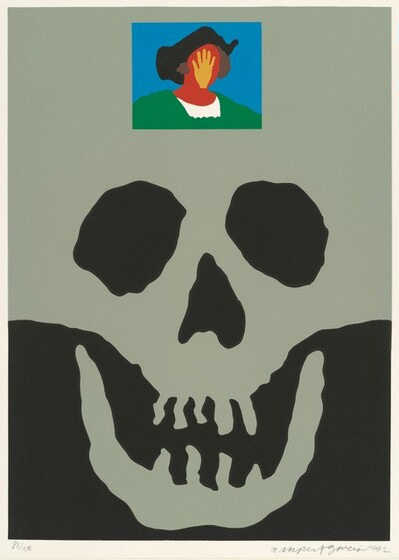

Rupert García, Calavera Crystal Ball, 1992, National Gallery of Art

This progression from one “ism” (like Impressionism to Abstraction) to the next one is entrenched in the linear, European Enlightenment notion of “progress.” This narrative of progress is also an intricate part of American history. The Manifest Destiny narrative, personified in this 1872 allegorical painting by John Gast, glorifies Western expansion while ignoring the erasure of Native American and Mexican -Americans while triumphantly celebrating the supremacy of “rational” Western thought. What this painting also ignores is that much of that Western expansion, what is now California, Nevada, Utah< Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado was ceded to the U.S. in 1848, historical proof that American history is and was Latinx history as well. I

*If the history of the Southwest intrests you this book by my former Latin American History Professor David Weber is vital reading

Like History, museums are also entrenched in colonial and imperialists legacies, in fact most, If not all of the “important” museum collections in the Global North came from wealthy donors who benefited from the colonial extraction and theft of the Global South. In one example, Sir Hans Sloane, a doctor and collector, purchased his vast collection (the foundation for the British Museum) with the profit from his wife’s slave plantations in Jamaica.

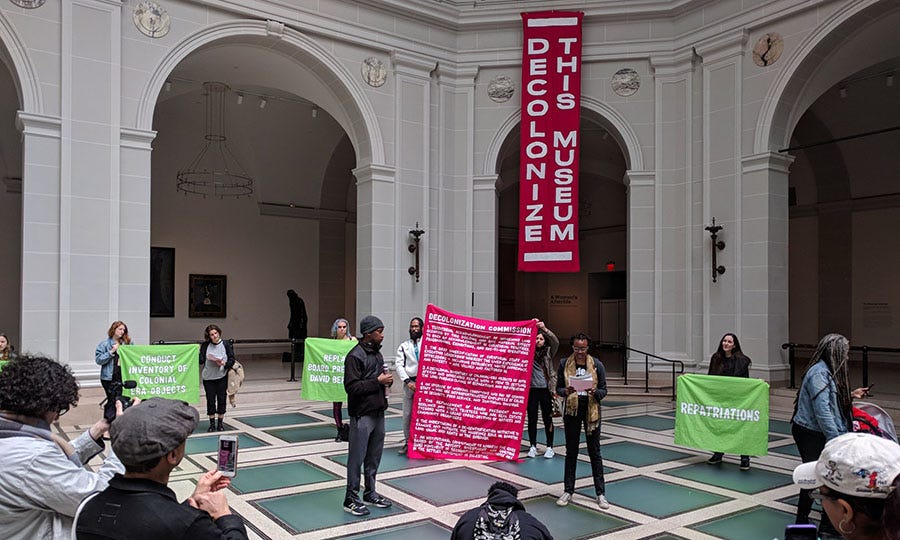

Recently there has been a global push towards repatriation and decolonizing. Institutions all over the world are working towards making their collections more diverse and to initiating a complicated process of returning artifacts that were looted during the era of imperialism. Yet many people who visit institutions like the British Museum, the Louvre and the Met which are filled with objects of dubious provenance (the history of ownership of a valued object or work of art or literature) are unaware of the colonial implications of collecting. This is something many activists, artists and scholars are working to change.

Decolonize This Place protest, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 2018. This demonstration was in response to the museum’s appointment of Kristen Windmuller-Luna, a white woman, as consulting curator for its African art collection. According to Frieze, “Decolonize This Place called the hire ‘tone deaf’. The open letter called for the museum to create a ‘decolonization commission’ which would acknowledge ‘the museum’s will to redress ongoing legacies of oppression, especially when it comes to the status of African art and culture’.” Here is another example, this time in Belgium. Also this summer, a ground-breaking exhibit in Spain, Colonial Memory in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collections, attempted to reconcile the violence and reality of musuem collections.

But I digress, the art of Latin America has recently had major wins, especially with the current iteration of the Venice Biennale, aka the Olympics of the art world. This event has great influence on the the art market, curators, critics, collectors, and dealers. For the first time since its inception in 1895 it was curated by a Latin American, Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa. And he made sure Latin American Art took center stage. Approximately one third of the artists represented at this Biennale are from Latin America! That translates to over 100 artists, about 24% of the show, representing sixteen countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Mexico, Guatemala, Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, and Haiti.

This year’s Biennale, aptly named “Foreigners Everywhere,” is proof that decolonizing is here to stay. “Foreigners Everywhere” is a very large show, and for the first time ever, most artists come from the Global South. (P.S. this term refers to countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific region, and it is a less offensive way to refer to lower GPD countries than “third world.”) Pedrosa’s curatorial vision for the 60th Venice Biennale has four conceptual "pillars:” the Foreigner, the Queer, the Outsider and Indigeneity.

For Pedrosa, the condition of foreignness is projected onto and embodied by not only those who are “immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, or refugees,” but also queer artists, who have put paid to gender boundaries and have often been persecuted or outlawed for it; outsider artists existing at the edges of the art world, if they are admitted at all; and Indigenous artists, who are “frequently treated as [foreigners] in their own land."

The Biennale comes after a period of growth in the commercial Latin American art market. It has amplified as certain artists have “crossed over” to the realm of bonafide art world stars (the most expensive painting ever sold is Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450.3 million in 2017). The highest paid work for a female artist is Georgia O'Keeffe at $44.4 million, and the runner up… FRIDA KAHLO! Not surprisingly since she is by far the most recognizable Latin American artist ever. In 2021 at Sotheby’s, her 1949 self-portrait, Diego y yo, sold for $34.9 million, the highest paid for a work by a Latin American artist at auction. The work was purchased by Argentine real-estate developer Eduardo F. Costantini and in a full circle moment it was included in this year’s Biennale, I think seeing so much Latin American art on display would have made the very anti-imperialist Frida very happy. The art market category for Latin America only began in the late 1970s, when the first specialized auctions of Latin American art at Sotheby’s and Christie’s began.

But in the case of U.S. based Latinx art, the race for equal “market value” has recently gained traction thanks to more inclusive museum practices and large grants. Most notably this five million dollar Advancing Latinx Art in Museums (ALAM) grant. This is necessary considering only 2% of all philanthropic giving goes to Latinx causes. According to 2020 Census data, there are 62.1 million Hispanics living in the United States, that is almost 20 percent of the total U.S. population. In Miami where I am penning this essay it is 72%!!

These conversations about Latinx art need to happen considering 80% of the leadership in American art museums — curators, directors or education program heads — was white non-Hispanic in 2019, as this historic Mellon Foundation survey illustrated.

“We know people of color are less likely to feel welcome in museums than those who are White. We know historical collecting practices have favored the art and cultural works of men of European descent.” - Mellon report

Rachelle Mozman Solano:

“My mom is from Panama, and I really wanted the work to be focused on Central America and the environments and backgrounds to be colonial homes. She was my first subject, really the first person I pointed the camera at and was like, ‘oh, there’s something really deep here.’ I think it was that she was my biggest enigma. I just could not understand my mother. So I feel like a lot of my work with her is about trying to understand her. She’s just very enigmatic, odd, and eccentric and traumatized.”

I really love this photo for it’s blatant reference to the issues of race and class in Latin America. Many people in the U.S. are unfamiliar with the social hierarchies of Latin America, since even the discussion of race in white America makes many uncomfortable. In fact that reluctance to talk about racism is one of the reasons that Dávila in her book Latinx Art, attributes to “why there is so much silence on Latinx identity, and why there was no space to talk about this racism.” She adds, in an interview about the book, that “the official script about the art world does not allow all these voices.”

In conclusion, I want to take a moment and be a cheerleader, to talk about some major gains in the amplification of Latinx art in the U.S…

A turning point was the appointment of E. Carmen Ramos as chief curator and conservation officer at the National Gallery of Art last year. She is the first person of color and woman in that role. And dear reader, she is a force (I knew her in the 90’s were both in grad school at the same time!) She also appointed Natalia Ángeles Vieyra as the National Gallery’s first-ever Curator of Latinx Art. This is a real milestone, considering the first Latina ever appointed as curator of Latin American at U.S. museum (UT’s Blanton) was Mari Carmen Ramirez (another University of Chicago alum) in 1988.

Other recently appointed Latinx curators include:

* María Elena Ortiz who was made curator at the Fort Worth Modern in 2022.

*Raphael Fonseca joined the Denver Art Museum in 2021 as the Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Latin American Art.

*Colombian curator José Roca is the inaugural curator of Latin American and Latin Diasporic Art at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

*Mia Lopez is the first curator of Latinx art at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.

*Marcela Guerrero is not only the first curator with a focus on Latinx at the Whitney Museum, but she will be one of the two curators for the 2026 Whitney Biennal.

*Gilbert Vicario is Chief Curator of the Pérez Art Museum Miami.

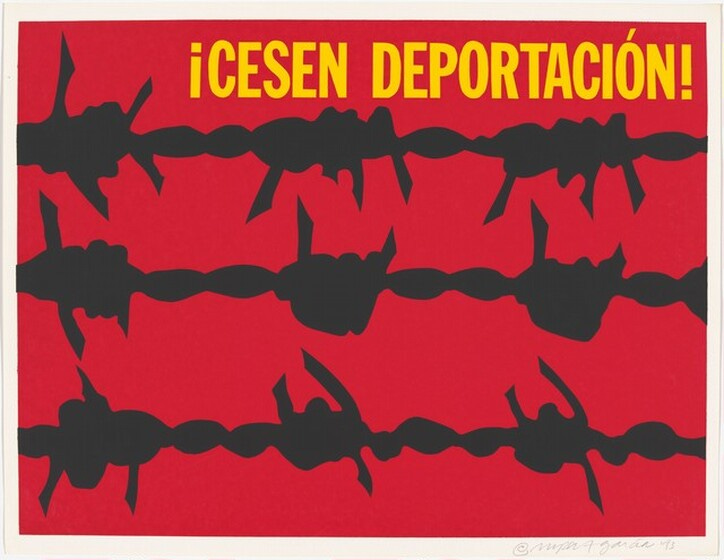

Rupert García, ¡Cesen Deportación!, 1973

In her book Arlene Davila says suggests that the term “Latinx” is a productive category “for revealing how matters of class, race, and nationality are operationalized in contemporary art worlds.” I think it works for now. No term is perfect, and all of them run the risk of looping all Latin cultures as one monolithic stereotype, and for this reason I think conversations around identity need to happen often, especially since we are vastly underrepresented in most industries, including our government. We must acknowledge race when speaking of Art History, museums, the art market and anything mainstream, which is code for white. Art holds power, one that can start shifting the stereotypes and racist tropes that most Americans see in film and television (and in the rhetoric of bonehead presidential hopefuls like orange man.) Latinx characters on screen are often depicted as immigrants (24%), low-income (also 24%), violent criminals (46.2%) and angry or temperamental (40%). As a Gen X’er I want to end with one of the 1970’s and 80’s most hilarious and enduring characters which signaled “Mexican” and Latin for pre-internet pop culture, Cheech and Chong… Turns out Cheech is an influential advocate and collector of Latinx art. We need more collectors and institutions to do the work and enunciate, loudly, that Latinx art IS American art, and that it deserves attention all year, not just during “Hispanic” heritage month.

Great observation

Always so insightful!

This is such a rabbit hole spiral! Here I thought Hispanic meant those who were born, or descended, and spoke Spanish in America.