Decolonizing Art at the Venice Biennale

The radical re writing of colonial history via Art at the Benin and Spain pavilions.

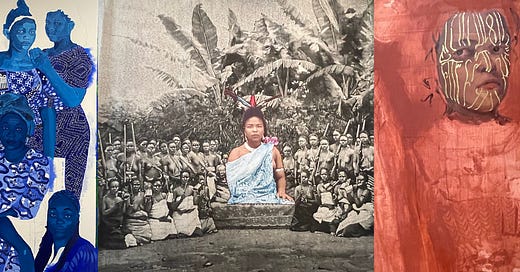

Image 1 (Left to right, Moufouli Bello, Ishola Akpo, & Sandra Gamarra Heshiki)

Foreigners Everywhere, aka the 60th iteration of the Venice Biennale was ground-breaking because it de centered Western contemporary art in favor of a decolonized and radically inclusive narrative. For the first time in over a century a Latin American curator, Adriano Pedrosa (the artistic director of the São Paulo Museum of Art) oversaw this sprawling global exhibition in which 88 countries participated. When asked about his goals for the Biennale, known as the Olympics of the Art World, Pedrosa stated: “I wanted to use this platform to give visibility to particular topics and themes—to the Latin Americans, the foreigners, the Indigenous, the queer and the artista popular, or the Outsider artist.” In this Biennale he succeeded in not only highlighting Latin America (about one third of the artists were from the region) but also in showcasing an unprecedented amount of formerly marginalized artists from the Global South. Since the Biennale’s inception in 1895, this iteration featured the largest number of indigenous artists ever, including the U.S. who exhibited the art Native American Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw and Cherokee descent.)

According to art critic Aruna D’ Souza, Pedrosa’s most radical tenet was “the refusal to center what we used to call the West. His rejection of art-historical hierarchies like art/craft and insider/outsider/trained/untrained artists, and his choice to avoid, for the most part, artists represented by blue-chip galleries or too familiar on the art-fair circuit, constitutes a rejection of traditional, Euromerican-driven gatekeeping mechanisms"

As the world’s most influential exhibition of contemporary art, an artist’s participation in the Biennale is a major boost to their career. But for so long what was included in the exhibit, and in the upper echelons of “modern art,” was dictated by colonial hierarchies and proximity to cities like New York or Paris. The colonial narrative of “modernity” has long been told as one of superiority and progress over anything deemed “un-modern” or “primitive.” Since the dawn of the Colonial era in 1492, the European narratives of modernity and progress were predicated on “othering” the colonized. And for that matter, decolonizing this racist concept was one of the aims of this Biennale. Most of the 331 artists featured in the Biennale delved into the ongoing legacy of colonialism in their art work, making this Biennale crucial to understanding the direction of current global curatorial tendencies.

But while the Global North is present, it does not speak—in Foreigners Everywhere, it’s been put on mute, so we can finally hear the rest of the world instead

-Aruna D’Souza

The fact that many artists from former colonies represented colonizer countries like France and Spain at this Biennale was revolutionary. Martinique- born Julien Creuzet not only represented France but he launched his entire multi media project across the globe in the French Antilles rather than in Italy. Similarly, for the first time Spain also featured an artist from a former colony, Sandra Gamarra Heshiki (B. 1972) a mixed-race woman of Peruvian-Japanese descent.

Her project, called the “Migrant Art Gallery” (Pinacoteca Migrante) not only rejected the linear telling of colonial history, it questioned the very institutions that traditionally define culture, namely the European museum. Broadly speaking her work explores themes of racism, forced migration, oppression and the extractive nature of colonialism.

Image 2. Sandra Gamarra “Miscegenation Masks V”

Image 3, Frans Hals, 1640, Family Group in a Landscape

Her painting Mestizo Mask V (image 2) is a reinterpretation of Dutch Golden Age painter Frans Hals’s 1640, Family Group in a Landscape (image 3) from Madrid’s Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. In the original the African servant almost disappears into the background foliage, his dark features contrast against the fussy, white starched collar. But in Gamarra Heshiki’s version she inverts the contrast, and the Europeans fade into the red hued back ground while the servant’s black skin is in the foreground, in color. To further drive her point she includes collaged images of contemporary Africans in the four corners of the piece. She also adds symbolic 3D textiles to hone in on the themes of forced migration. She incorporates a metallic thermal blanket given to migrants rescued at sea, and a Ghanian textile scrap that eradicates the female figure on the right. Also the use of gold is perhaps an allusion to the extraction of minerals. To finance its imperial expansion, Spain mined over 100 tons of gold form the Americas during the early colonial era (between 1492 and 1560.)

Copying the style of traditional European art is an integral part of Gamarra’s work, and in reproducing the past she is also re writing the present. The tradition of copying and replicating is a hallmark of the Spanish colonial empire where entire indigenous cities were leveled and made to resemble European ones. Native artists were taught to copy religious art as part of their forced conversion. But Gamarra’s copies are an act of subversion. In fact during my visit to this pavilion an enraged Spanish couple stormed out once they caught on to the disruptive narrative that centered the displaced.

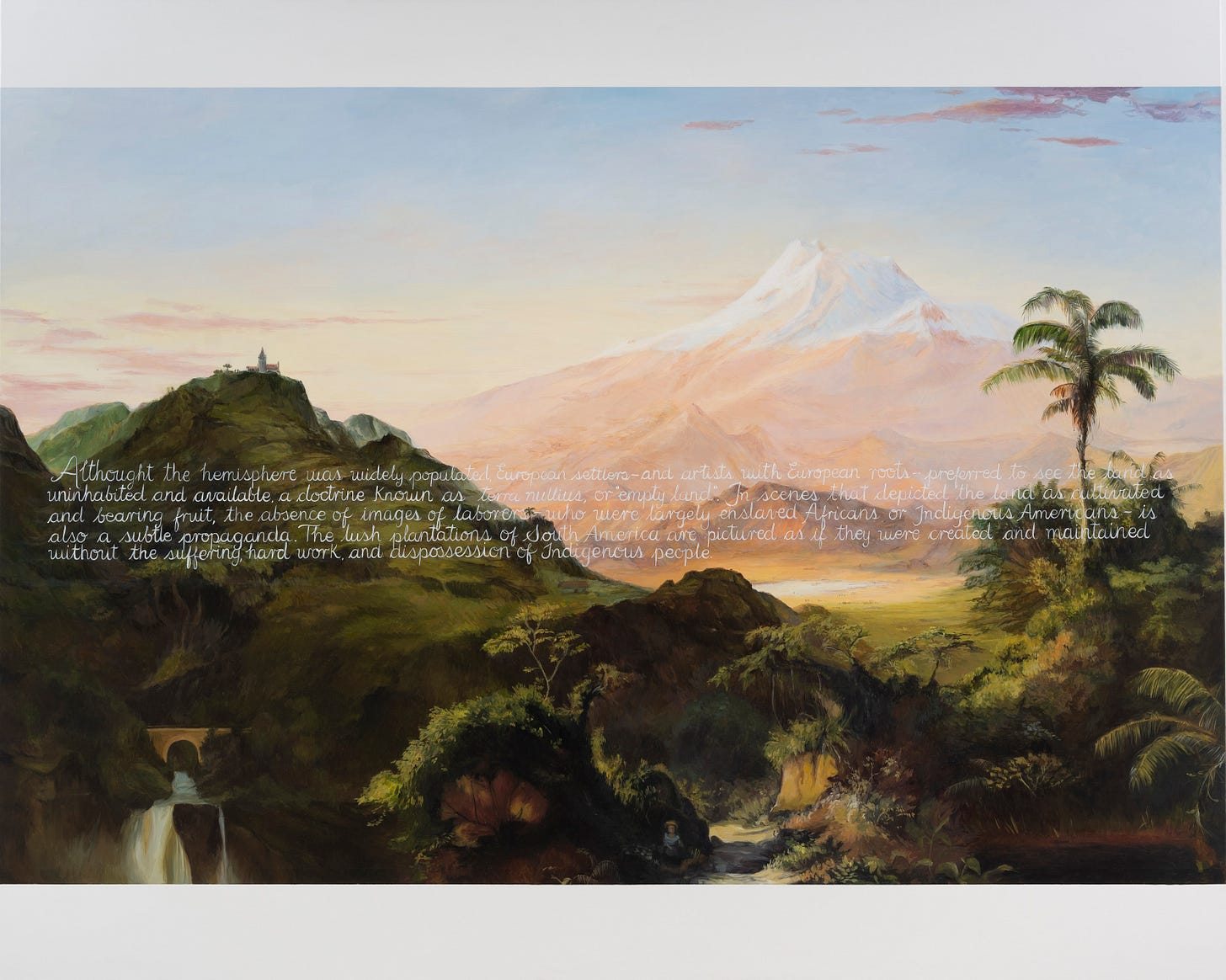

Another theme in her Migrant Gallery deals with the extraction of raw materials like gold and the use of landscape painting as symbolic of “virgin” lands ripe for conquering was part of the colonial project. Aside form landscapes, her comprehensive, immersive installation of more than 150 pieces includes drawings, ceramic, figure paintings, and etchings. Meant to emulate a traditional “fine art” European museum, it instead subverts it upon careful viewing and reading of her texts. Take the painting below (image 4) atop the landscape painting she includes this academic text:

Although the hemisphere was widely populated, European settlers - and artists with European roots- preferred to see the land as uninhabited and bearing fruit, the absence of laborers who were largely enslaved Africans or Indigenous Americans- is also a subtle propaganda. The lush plantations of South America are pictured as if they were created and maintained without suffering and hard work, and dispossession of Indigenous people.

Image 4, Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Virgin Land, 2023 Oil on canvas

Image 5, Frederic Church, ‘Mount Chimborazo at Sunset,’ c. July 1857

Her landscapes “copy” XIX paintings like those of American artist Frederick Church’s “Mount Chimborazo” (image 5) which were popular during the late Colonial era and exhibited at places like the MET in New York. They were integral in crafting narratives of nationhood and expansion, but Gamarra views them through a lens of environmental colonialism that call attention to the colonial roots of the current climate crisis. (Read this epic article to gain wider awareness on this subject.)

Once again she uses mimicry, or copying as an act of subverison. Gamarra also references the hierarchies in museums which traditionally signaled the art of the Americas as inferior, for instance in Spain it was housed at the Museo de las Americas and not at the Museo del Prado. At the Met for many years it is was exhibited under the broad category of “Art of the Africa, the Americas and Oceana.” This is an institutionalized way of othering, this is the age ole divide between art/artifact, or art/craft where the latter, the crafts are traditionally indigenous and not Western and therefore not considered “High Art".”

Post colonial critic Homi. K. Bhabha in his seminal book The Location of Culture, states that “imitation” or mimicry subverts the colonial state by normalizing it in a way that it no longer seems superior or seamless. And this re writing of the colonial narrative is also brilliantly achieved in the Benin pavilion…

Benin

Like Ethiopia, Tanzania and Timor, it is the first time that Benin participates in the Biennale. This is a milestone considering an estimated 90% of cultural artifacts still remain outside of Africa. The exhibit was helmed by Nigerian curator Azu Nwagbogu who took one year to explore the themes of ancestral memory, loss of biodiversity and economic disparity by meeting with elders who concluded that “the reason the world is out of kilter is because we’ve embraced this other sort of rootlessness that is lacking in care.” These “cultural custodians,” included historians, chief priests, and voodoo masters whom he called, “the bearers of information or knowledge.” He described this approach as an anthropology. He refers to the Republic of Benin, formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey as “the birthplace of voodoo and an ancient culture revered for its matriarchy,” and his aim for the exhibit is “for viewers to grasp the essence of African/ Benin feminism, rooted in histories that precede contemporary Western feminist trends…Ultimately, the exhibition serves as a catalyst for contributing to the reversal of centuries of epistemic injustice and violence perpetrated against Mother Earth, mothers, women, and young girls globally.”

The name of the exhibit, Everything Precious is Fragile, comes from the Yoruba maxim Eso l'aye which translates as “the world is fragile.” It is an antidote to the dismal state of our current world according to what the aforementioned elders told him, caused by women having “been displaced from their traditional role of equality and power in society.”

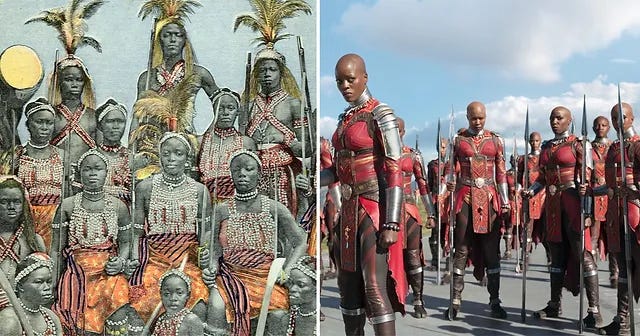

As stated the exhibition explores the history of the West African, French speaking Republic of Benin. Here is a bit of its colonial past: the Portuguese first explored its coast in 1472, then in the 17th century the Dutch, English, and until France took over 1894. The region’s principal export before the mid-19th century was slaves, it was known as the Slave Coast of West Africa because of the high number of people sold and trafficked to the Americas.

(Fun fact: the all-woman Dora Milaje regiment featured in Black Panther is based on the Dahomey warriors who lived in the royal palace alongside the king and his many wives in a mainly woman-dominated space)

“Everything Precious Is Fragile” also delves into the contemporary realm of Gèlèdé- a West African social philosophy which views life as delicate, and calls for harmony with the natural world, it is associated with the feminine, a principal perfectly interpreted by this colossal tapestry:

Ishola Akpo, “Ìyálóde,” Jacquard, double satin weave

This full-color, massive tapestry (which has its origin in early 19th century France with the invention of the Jacquard loom by Joseph-Marie Jacquard) is by multimedia artist Ishola Akpo (born 1983 in Ivory Coast, lives in Benin.) His inspiration for the feminist piece was the reign of 18th-century warrior queen Tassi Hangbe who led an all-female army - the Agodjies, known to Europeans as "Amazons.” These women warriors were considered ahosi, or wives of the king, but in this tapestry a superimposed female queen reigns! The artist fused two tapestries, the black and white one from an archival photography where a male chief was originally pictured, and instead he layered another full color tapestry of a queen using silkier threads. Like Gamarra’s work, Akpo subverts the colonial narrative of Western patriarchy but by utilizing European art historical language, what Audre Lorde called the “master’s tools,” in this case French Jaquard tapestry.

Égbè Modjisola by Moufouli Bello

“I only paint Black women, and blue allows me to cover all the shades of Black skin in a symbolic way.

I'm Yoruba by origin and Indigo is a spiritual color for my people.” -M. Bello

Born in 1987, International Labor Lawyer turned multimedia artists Moufouli Bello large-format paintings like the one seen here call attention to female inequality, injustice and the impact of debt on African women. Her indigo-tinted portraits, showcase the iconic Yoruba patterns found on women’s clothing. And in their presence one can feel the symbolic power of textiles and the color indigo blue. According to the artist, “the memory of my emotions brings me back to that colour, which, for me, is associated with benevolence, security and home. Basically, the total freedom to be and to exist.” The women portrayed in her work also subvert the male, colonial gaze where woman are “invisible and gagged,” instead her figures tower, forcing the viewer to look up. In an interview with CNN she said “an objectifying gaze upon them is mirrored with their strong self-articulation and a reclaiming of autonomy and authority…I’ve found that art can be used as a tool to denounce things, to educate, because (it) doesn’t involve direct confrontation and allows the artist to express herself without putting her person first.” Her radical revision of history involves restoring a feminine order to a chaotic, displaced post-colonial world.

I will conclude (thank you for hanging on!) with a note on color as sacred, as articulated in Micheal Taussig's seminal book “What Color is the Sacred” which I cannot recommend enough. Both the art of Spain and Benin in the 60th Venice Biennale address the nature of colonial power through their use of color, red and blue respectively.

Indigo which was used as currency during the colonial era, was more “powerful than the gun" according to author Catherine McKinley. The color is inextricably linked to the slave trade, as one length of this cloth was traded for one human body. Indigo, along with cotton and tobacco, were the cash crops that made slave traders extremely wealthy and helped build European empires. In the 1700s the profits from indigo superseded those of sugar and cotton. Often understudied, this commodity powered the trans-Atlantic trade routes. Women in Africa were instrumental to the slave trade, often gaining wealth, and political power through their knowledge and trade of this natural dye.

Similarly, Gamarra’s choice of red as the unifying color in her “Migrant Art Gallery” also refers to the sacredness of red in the cosmology of Andean textiles where it is symbolic of conquest, blood, and divine rulership. Red is THE prominent color in ancient textiles from South America, and it can still be found all over the region today. In my fieldwork in the region I can attest to the continued belief in the power and sacredness of color for indigenous weavers, their circular way of viewing the world is stark opposition to the linear, extractivism of Western capitalism. In their rebuttle of patriarchal Western “rational” thought in favor of the indigenous the artists I mentioned mark a curatorial shift in the global art world. As the aforementioned quote by Aruna D’ Souza stated, if only for a couple of months (the Biennale ends November 24th) at the Biennale, the art of the Global North does not lead the conversation, instead “it’s been put on mute, so we can finally hear the rest of the world,” and that radical act of decolonizing is long overdue.

P.S. Please give me a like or a comment on the app, and if you enjoy my work consider becoming a paid subscriber, in 2025 I will add a paywall to some posts as it really is very laborious to research, so thanks again to the people to support my work!

Great job on this Vero!!!!

What a superb job 👍🏼it’s worth the time to invest in its reading, like learning about a new art world 💝