Reclaiming Memory, Resisting Extraction, and Reimagining Colonial History: Women Artists at the Intersection of Climate and Social Justice

Sandy Rodriguez, Carolina Caycedo, and Andrea Chung

Hello friend,

I have not written in a while. To be honest, I have started and stopped various essays so many times, but the news, life and the state of the world paralyze me. Here is a sad reality, both the arts and the environment are both under siege. This week “senior leaders and other employees left the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) en masse…This news comes on the heels of the Trump administration effectively shuttering the agency, with a proposed budget proposal cancellation for the 2026 fiscal year and redistribution of said funding. We are living in a dystopian country, and if we are paying attention we know this means culture and the earth are both at risk. Now is the time to support artists who truly engage with critical thinking and history, two things this administration wants us to forget. And so I will talk about some of my favorite contemporary women artists whose work addresses the colonial legacy inherent in environmental and social injustice.

As far as sustainability goes, the art market is far from innocent. (Not-so-fun-fact: the amount of private jest that fly into Miami on the week of Art Basel is close to the amount at the Super Bowl.) In 2021, the global art market generated an estimated 70 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent — more than the annual emissions of countries like Austria or Greece. Transporting artworks by air, waste from single-use materials, plus the volume of energy consumption that large-scale exhibitions and fairs contribute to in terms of ecological harm is vast. Some artists offer alternative models that decenter profit and prestige in favor of sustainability and equity, as Carolina Caycedo states:

“Art has the possibility and the responsibility to create counter narratives.”

Climate change, plastic pollution, fast fashion, and the carbon footprint in the production, exhibiting and storing of art are manifestations of systems built on exploitation. Every day, 2,000 garbage trucks worth of plastic are dumped into our waterways, and the textile industry alone wastes the equivalent of 86 million Olympic-sized swimming pools of water annually. These statistics are not abstract — they are the material consequences of extractive capitalism. But something that is often lost in the storytelling behind why sustainability matters is the root cause. Art offers a pedagogical tool for gain a deeper understanding of the systemic causes.

In this excerpt from the soon-to-be-released book “Black Earth Rising” by Ekow Eshun he explores the inextricable ties between the climate crisis and the extractive economy of the Spanish colonial era. He “traces the roots of climate crisis back to the 15th century and the creation of the vast agricultural estates that were a defining physical feature of European annexation of the New World. With the plantation system came transatlantic slavery, as well as the large-scale land clearing and extensive deforestation that significantly altered local ecosystems”

Image on top: Raphaël Barontini, (b.1984), “Au Bal des Grands Fonds,” 2022. The artist feels a connection to others whose life has been uprooted by colonial displacement, and whose identity “has been forged by encounters with other cultures through processes of creolization. These processes were described by Martinique-born French philosopher Édouard Glissant as a complex entanglement of different cultures forced into cohabitation, as in the case of the Antilles and other countries in the Caribbean.

Image on the bottom: Andres Sanchez Gallque’s “Three Mulatto Gentlemen of Esmeraldas,” painted in 1599 is the first European-style portrait painted in Colonial Latin America. It depicts a father, Francisco de Arobe and his sons, Pedro and Domingo. Don Francisco was a political leader and the son of an escaped African slave and an indigenous Nicaraguan woman. He governed an area of coastal Ecuador populated by African descendants of slaves. The painting was made as a gift for King Phillip II of Spain, as proof of Francisco’s supposed allegiance to the Crown. Chances are the painting never reached the King, but today it strikes me as performative mash up of “regal” Spanish court fashion and elements of “native” accessories like the jewelry and nose pieces the men wear.

European colonialism—the act of exploiting land and resources on which others are already dependent—didn’t only devastate the local communities living on the lands settler-colonizers stole. Colonialism also devastated ecosystems. -Yessenia Funes

This essay will explore art of artists Sandy Rodriguez, Carolina Caycedo and Andrea Chung who address climate breakdown while rewriting new narratives of historical and ecological memory. By bridging the past and the present, their work reclaims erased knowledge, reimagines future possibilities, and transforms spaces of trauma into sites of resistance and healing. They engage in socially and ecologically grounded practices that reshape art history through fieldwork and non-linear narratives that center Indigenous knowledge, local materials, feminist critique, and a resistance to colonial structures. Their practices recognize that knowledge embedded in land and tradition predates, and often contradicts, Western capitalist frameworks.

Los Angeles-based, Chicanx artist and researcher Sandy Rodriguez’s (b.1975) prescient, interdisciplinary process includes the foraging and making of paint from minerals and botanical specimens. Her work is “sustainable” on many fronts, she uses pigments and materials which were used in the Americas prior to 1492, showing the viewer that despite centuries of colonialism these methods persist, or rather resist as the title of her new show "Currents of Resistance” implies. Deeply informed by her long career in museum education, her work engages with colonial archival material, specifically the Florentine Codex, a sixteenth-century ethnographic document compiled by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún.

Mexica Jaguar and eagle warriors, Book 2, Florentine Codex, 1577

My chosen medium is site-specifically sourced, hand-processed earth, plant, and insect-based watercolor on sacred – once outlawed – amate paper, a testament to the artistic traditions of the Americas. Recovering the medicinal and aesthetic uses of local plants and pigments enables my work to support healing and awareness building of current issues. The labor-intensive process synthesizes interdisciplinary research – this includes rigorous field study, historical, and ethnobotanical – with the urgency to address the crisis in the United States and US-Mexico Border.

-Sandy Rodriguez

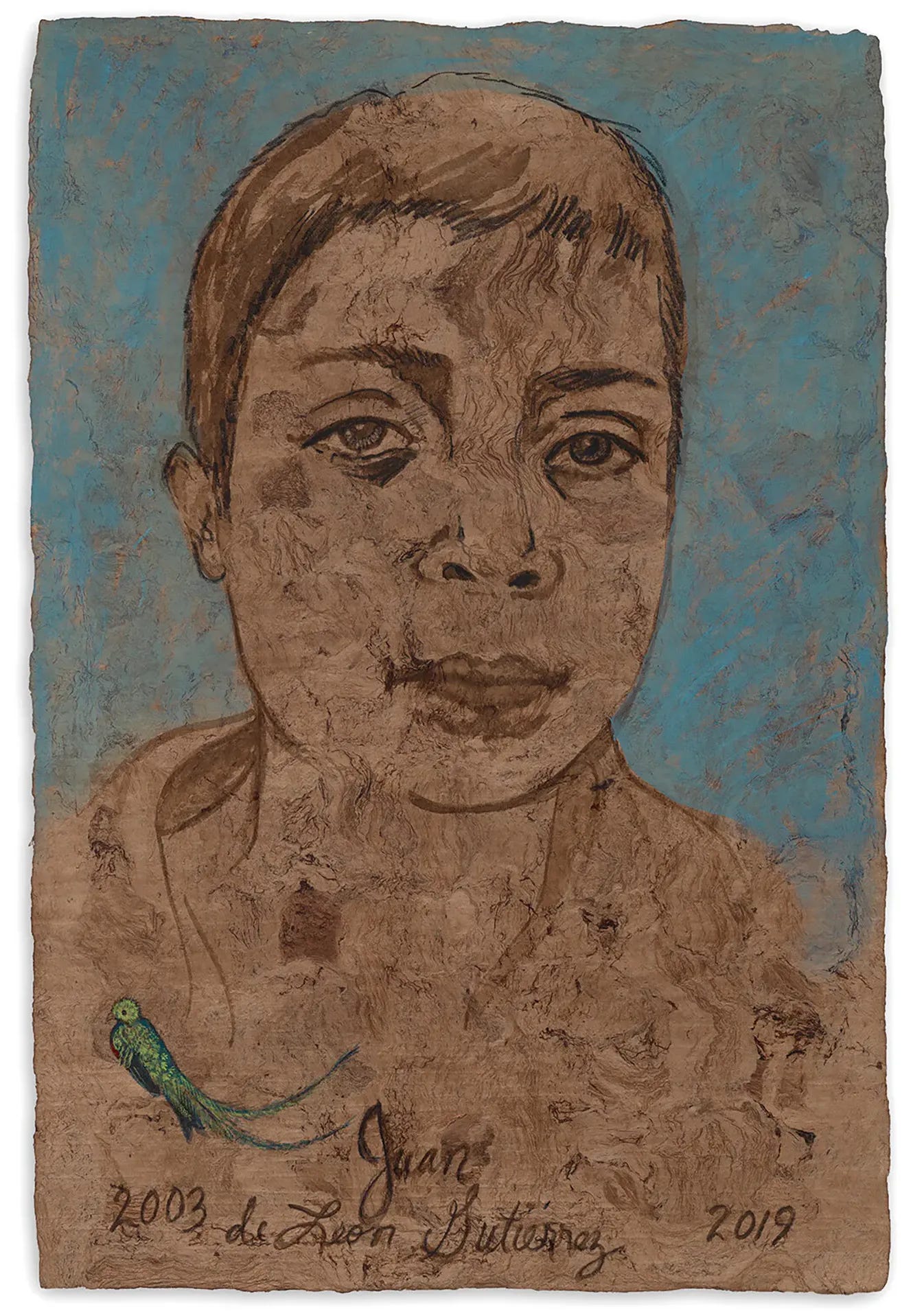

Sandy Rodriguez, Juan de León Gutiérrez (age 16, a child migrants who died in federal custody between 2018 and 2019), 2019. Hand-processed watercolor on amate paper. “Each face is carefully traced in walnut ink, the brown textured shades of the amate paper gesturing both to bark and earth. The full names of each child are written underneath, as are their years of birth and death. A quetzal bird in brilliant green hues is perched on six of the portraits, its meaning manifold: a protective talisman and the national bird of Guatemala, from where those children hailed. According to the artist, the bird “dies from sadness when caged.”

This portrait of a migrant children who died in US Customs and Border Protection custody is made using the same pigments and bark paper as the aforementioned colonial codices. The narrating of a present-day act of political violence is told using indigenous techniques- this atemporality is a hallmark of Rodriguez’s work. Her reclamation and use of ancestral knowledge is revolutionary.

Amidst our current socio-political climate, Chicanx artist Sandy Rodríguez’s bold and timely exhibition in Sarasota, Florida is in and of itself and act of resistance in a state increasingly branded as a “bastion of anti-woke” politics. It is a poetic multi media exploration of history and cultural resilience in the Gulf of Mexico, from the early sixteenth century to the present. In direct tension with former President Trump’s campaign to rebrand the area as “The Gulf of America” — a move that attempts to erase its Spanish Colonial and Indigenous past — Rodríguez’s work reclaims the Gulf’s deep historical and cultural ties to Mexico and broader Latin America. Her art counters this erasure with precision and beauty, restoring memory where dominant narratives would prefer silence.

Rodríguez’s interdisciplinary process is profoundly atemporal. On a single sheet of Ámate bark paper — a material once banned by Spanish colonial authorities for its association with Aztec codices — she addresses both contemporary crises and enduring colonial legacies. The use of amate is not simply symbolic; it is an embodied form of resistance, reconnecting with Indigenous technologies of knowledge and storytelling. Her compositions collapse linear time, layering the present onto the past in intricate cartographic and painterly language. Her work is visually lush and politically charged — where acts of survival, migration, and defiance are meticulously recorded in natural pigments thats she produces herself from native plants, insects, and minerals.

Exhibiting this work in Florida is especially significant. It asserts the enduring presence of Latinx and Indigenous cultures in a state where political forces seek to suppress them. In a place where education is under siege and cultural memory is politicized, Rodríguez offers a luminous counter-archive — a visual codex of resistance that insists on remembering otherwise.

CAROLINA CAYCEDO:

Like Rodriguez, Colombian-born Caycedo plays with non linear narrative structures and addresses contemporary neocolonial politics…

“I understand a work of art not as a closed circle but as a spiral that can shoot in different temporal, geographical, and intellectual directions.” CC

Carolina Caycedo, Nuestro Tiempo/Our Time, 2018, hand-dyed artisanal fishing net, metal chain, palm mat, wool charm, and tambourine. “Weaving a fishing net or casting a net into a river speaks about accumulated and embodied knowledge passed from generation to generation, which has traditionally been stigmatized by Western canons. Extractive and capitalist projects break this transmission of knowledge.” -CC

Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas series utilizes hand-dyed fishing nets and symbolic objects collected through community-based fieldwork to critique symbols of state sanctioned oppression like dams. Her work transcends the gallery space, embodying a social practice that exists in rural landscapes, riverside gatherings, school classrooms, and intimate domestic settings. “I understand a work of art not as a closed circle but as a spiral,” Caycedo states, a metaphor that captures the layered complexity of her work and its ability to expand in different directions — geographical, historical, intellectual, emotional. This approach is inherently feminist, deconstructing extractive logics that link colonialism, patriarchy, and environmental exploitation. “Health, knowledge, labor, and, ultimately, life have been historically extracted from women’s bodies in the same way fossil fuels, genetic codes, and energy have been extracted from the land,” Caycedo argues. This parallel between ecological and bodily violation reveals the deep interconnection between feminism and environmentalism. The work proves that it is impossible to isolate the climate crisis from patriarchy.

Caycedo’s examines environmental justice and the impact of dam building in her native Colombia. The construction of dams -large-scale civic project enacted by governments and multinational corporations- privatize communal resources like rivers. Caycedo aligns closely with affected communities through her “spiritual fieldwork” with environmental activists aimed at reclaiming of indigenous knowledge systems via systems of care and healing, not coercion.

“The work is a criticism of the greenwashing of the energy transition that we are witnessing today. Yes, we need an energy transition, but we need a just and fair one, where the impacts of these extractions are not lived by people, communities and ecosystems in the Global South to enable the decarbonization of the North.”

Carolina Caycedo

Carolina Caycedo, Lead Intensive, 2025

For Caycedo the fight against extractive economics and feminism are deeply entwined: “health, knowledge, labor, and, ultimately, life have been historically extracted from women’s bodies in the same way fossil fuels, genetic codes, and energy have been extracted from the land, from plants and animals, from rivers. The logic underlying the oppression of women and the exploitation of the natural world is the same.” This is also echoed in the brilliant work of Sand Diego-based Andrea Chung…

Andrea Chung’s (b.1978) breath-taking recent exhibition “Between Too Late and Too Early" at Miami’s MOCA fundamentally challenged and expanded the way I see and write and think about art, climate change and colonialism. Her exploration of sugar, as a raw material that has a history of economic exploitation and forced labor, was especially poignant. After her graduation from MICA, she received a Fulbright Fellowship to study in Mauritius, a former sugar colony. The Dutch introduced sugarcane to Mauritius in 1639, later, the British took over Mauritius. Eventually the sugar industry employed over 90% of the population. Other themes her recent exhibit addressed was the neocolonial exploitation inherent in the tourism industry.

“I’m interested in material and process. That’s what drives my practice— the curiosity of knowing what I can and can’t do with a material, and finding that area in-between…Everything I use is, for the most part, ephemeral. I like that it’s ephemeral because the work needs to have its own history and its own lifespan. For me, those things are exciting. The subject matter is generally about the effects of colonialism on island nations, more specifically the Caribbean, although I don’t just limit it to the Caribbean.” -Andrea Chung

Andrea Chung, “Spectre” (2017), cyanotype on watercolor paper, with “Bato Disik” (2013), sugar, in the foreground (photo by Zachary Balber, MOCA North Miami)

Chung has spoken about her art as a vehicle to explore her family’s heritage, and her own identity as a mixed race person whose grandfather was Chinese stowaway who moved to Jamaica as a teen. “I always try to think about what it would have been like to have been seventeen, escaping a situation— like Trump, but it was Mao— leaving your entire family, not knowing where you’re going but just trying to get out, and then coming to an entirely different climate, culture, and language. And surviving. What does that do to you? I wonder how, psychologically, that changes a person.” Her paternal grandmother was a mixed race Jamaican. Her maternal grandmother was Chinese and Arawak and her father was Black and French from Martinique. In her work she explores how the sugar industry affected her own family:

“A lot of foods that were brought to the Caribbean to feed enslaved people—mango and coconut—are not native to the area and are full of sugar. Diabetes runs in my family, and my grandmother died getting her second leg amputated from gangrene. It felt like the right material to tell the story of my family in that region.”

Like Rodriguez her work is nonlinear in that she addresses colonial history but ties it into the present day. The same colonies that were exploited for sugar are currently ravished by a tourist industry catering to rich Westerners - think White Lotus.

“Caribbean artists often synthesize—or creolize—traditions, temporalities, and approaches to create global, multimodal, and transcultural forms. Thus, exploring their complex histories requires nonlinear strategies and new narrative form”

erica moiah james

Through interdisciplinary practices, rooted in Indigenous, feminist, and ecological frameworks, artists today are not only creating objects — these artists are creating portals. Openings for memory, for justice, for new ways of living with the Earth and with each other. Their work reminds us that art can be a form of resistance, a space for community, and a tool for imagining just and sustainable futures.

Above ⬆️

What a profound analysis of a subject affecting lives since colonial times. Due to unfair ambition, peoples and environment have been destroyed. Amazing to be able to express so much in art works. Masterful writing Vero, as always.